How do we memorialize an ongoing crisis that is being publically minimized and disavowed? How can we bridge the chasm between the millions of lives lost across the globe and the intimacy of personal and familial loss? And how can traumatic memory be transformed into activist engagement for social justice?

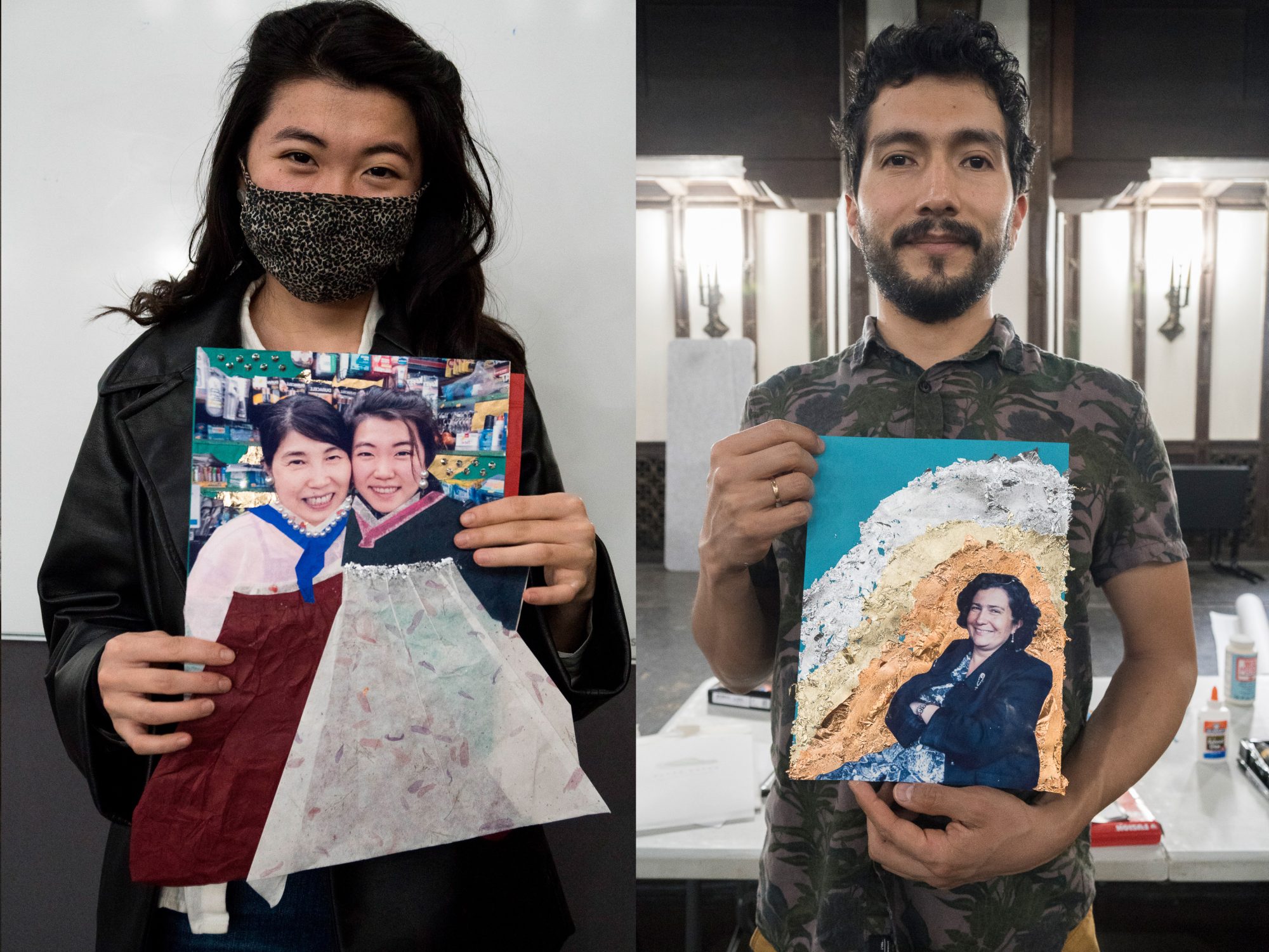

As we conceived the ZCMP, we realized that the monumental and as yet unprocessed events of the COVID-19 pandemic require their own mourning and memorializing practices emerging from multiple traditions, and forging new ones. We didn’t get to be together in prayer, participants said. In order to be restorative, memory practices need to overcome the isolation occasioned by the pandemic lockdown and the impossibility of joining with friends and family to mourn loved ones. Relying on Afro-Dominican traditions, participants from Washington Heights built two Altars to Beloved Neighbors at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, with candles, embroidery, decorated photographs and objects that served as reminders of loss, even as they honored the lasting contributions of those who died of and during the pandemic. [Altars]. ZCMP’s Imagine Repair exhibition also included an ongoing participatory memorial by artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, A Crack in the Hourglass. It provides that moment of accompaniment that we missed, allowing us to be present while images of lost loved ones are slowly being drawn with ink-like sand by a robotic arm. As the sand is reused for portrait after portrait, the images of the dead are intertwined in a space of communal mourning.

But memory practices in the midst and the wake of the pandemic also needed to make space for our anger at the institutional failure and neglect that caused so much more devastation than necessary. Sharing memories through storytelling, active listening, Theater of the Oppressed workshops, and other creative activities, we found, can help individuals and groups acknowledge and make sense of painful pasts and begin to heal from traumatic loss, both individual and collective. A major first step towards emotional recovery, the caring environment that fosters acts of testimony and witness can also become a platform for social transformation. As memory activates the past in a communal setting, it can also reframe it and imagine a different potential ending––one that can serve as a provocation for collective political engagement. Only thus can memory be reparative and oriented toward the future.

The fact that we can all come together with that shared trauma to acknowledge it, release it, and collectively see a way forward is a very beautiful thing.

Header photo: Sylvia Juliana Riveros Torres

Header photo: Sylvia Juliana Riveros Torres